Creative Language for Pupils with ESL

I was so pleased to be invited by Famida Choudhary to speak on the Teachers’ Talk Radio podcast for the UAE last Saturday. Working with pupils with English as an additional language has long been my passion, initially sparked during my 17 years working in The Caribbean. Because 14 of those years were dedicated to isolated small communities where everyone spoke entirely in patois, the experience and issues for reading, writing and communication reflected those of second language learners.

I will never ever forget being met off the plane on our very first arrival from our first ever flight in 1970 by a gentleman who greeted us warmly but we could not understand one word that he said in the 36 plus mile journey to our community. By the time of our arrival we had grown an escort of a number of youths in the backs of open trucks, who joined in our induction to our new home – all speaking in a seemingly totally foreign tongue. I well remember our fear and bewilderment, and our frequent whispers to each other of ‘What did he say?’ and ‘What do you think they are talking about?’ as we attempted to smile and nod sagely.

That must be similar to but far less intimidating than the experience for a young child of arriving in a classroom where everyone is speaking in a language foreign to them and where no-one appears to speak their language. What would you and I do if we went to a class in a faraway community and found it was all delivered in an unknown tongue? If we had eachother we would say exactly what the ex-husband and I said to each other – ‘What do you think they are saying? What must we do?’ If we were alone – we would sit in silence, probably in some fear and trepidation.

The cruciality of sitting new pupils who do not yet speak English with others who do speak their first language, or with whom they share a second or third language, should be self-evident and yet many teachers, believing they are acting in a child’s best interests, will separate those very children so that they CANNOT communicate in anything but English. This is not just misguided, it is unwittingly cruel.

When a teacher has completed the taught input of a lesson – or at intervals throughout the input if it is lengthy – ALL children should be given time for focused talk to discuss and agree what they have learnt from that input. This is as beneficial and empowering for first language English speakers as it is for those learning through English as a second or additional language. If all children cannot repeat what was taught, we must respond and clarify or simplify the input. If they can repeat the content, they are starting the process of embedding it and of clarifying meaning for themselves.

Equally, following the instructions for what is to be done by the children in a lesson, they should ALL repeat and agree with each other what the task or activity is. Again, a lack of recall or understanding would show that there may be inhibitors to executing the instructions and further clarification may be required.

These focused talk sessions are key to success for all children. For children new to English, they should preferably be in first language or a shared language, with increasing additions in English as the days and weeks pass.

The interesting outcome of this approach is, that ANY time children are to learn new sentence structures, new vocabulary or new phraseology in order to either improve spoken or written communication, the same approaches should be involved. How does the baby learn its first words? How does the toddler learn its first phrases and then simple sentences? It is through repetition and frequent practise – and through being steeped in talk. In silent homes, language development is delayed. Isolated children who do not learn to talk by age seven will never learn to talk – unless the isolation was psychological rather than imposed.

We learnt our first simple sentences through listening and repeating – over and over again. We widen our language banks through listening and repeating. We widen our vocabulary through listening and repeating or through reading and repeating in speech or in writing. We develop a creative voice through hearing and repeating – we develop oratory through hearing and repeating – all with quality modelling, explanation and interpretation to support us. That is called TEACHING.

Some of us were lucky and we learnt to talk confidently – code switching between restricted conversational codes and elaborated codes with ease as we chose – in the home with a family of talkers who steeped our lives in language through discussion, debate, argument, explanation and so on. Others of us were equally lucky if we entered an Early Years setting that compensated for a lack of these pre-school opportunities by constant and rich, focused talk. Some of us were never so lucky…

Research tells us that the average adult knows around fifteen to twenty thousand words, while the highly educated adult may know up to fifty thousand, but a proportion of the adult population only knows around twelve thousand words despite not having a special need or a disability. This can have a significant impact on achievement and life opportunities.

Teaching new vocabulary, including rich and emotive words, not only increases opportunity and enables wider decoding and understanding of more advanced texts but also impacts on a pupil’s ability as a creative writer or powerful speaker. The overlap between the skills that empower an orator and those that underpin a successful writer, including a wide range of sentence structures and vocabulary that are enhanced by suave features as identified in our Talk:Write Programme, enable teachers to focus on the teaching of these features to ensure success across and within the curriculum at all levels.

So teach words and structures proactively, use focused talk activities to ensure full understanding and the ability to successfully achieve any task required, and then use a range of enjoyable and interesting ‘games’ and activities to embed the strategies in long term memory and to practise using these features in a wide range of contexts – both oral and written. And know that the ‘power’ word in the previous sentence is TEACH. Always remember, when considering the potential of your pupils, the enrichment of the curriculum and the diverse experiences you are making available, that teachers make the difference, ergo:

‘YOUR TEACHING makes the difference – OR NOT…’

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

The Gift of the Gab

Yes – it’s true! I love to talk.

When asked to fill in my hobbies on any sort of form I always put:

talking; writing

Many is the time I have punctuated an input to teachers with the words;

“I was born talking and now nobody can ever shut me up. In fact I have to be shut in a cupboard at night and if you open the door a chink in the early hours, you will still find me standing there gabbing away…’

The dictionary gives the following definition for that well known idiom; the ability to talk fluently, glibly and persuasively, with enriched language.

The idiom “gift of the gab” refers to the ability to speak easily, confidently, and persuasively. It originated from the Middle English words “gob” (mouth) and “gabbe” (idle talk). The phrase “gift of the gab” itself emerged in the 1680s, signifying a talent for speaking.

The word “gab” itself has a history tracing back to the 13th century, with early meanings including “chatter,” “idle talk,” and even “falsehood”.

My mother used to say I must have kissed the Blarney Stone when I was born. Blarney Castle in County Cork was built by the great chieftain Cormac Dermot MacCarthy, son of Dermot McCarthy, in 1446. Dermot was renowned for his eloquence and those who kiss the Blarney Stone, which is set into the walls of the castle, are said to be granted the gift of the gab.

I have never been to County Cork and I have never – to my knowledge – kissed a stone (although I have tripped over a fair few) but I do love to talk and in Yorkshire we call that gabbing. And I do admit to being able to talk very easily, usually fluently and often persuasively, however the reasons for this are not stone kissing but rather – survival!

If you had grown up with 3 siblings who were all older than you, highly intelligent and highly articulate – in the days before TV when talking was the main leisure activity and at a level of enforced deprivation that meant everything had to be fought for and about and the entertainment of every evening was discussion and debate – then you would have had to learn rapidly to ‘hold your own’, ‘stand your corner’ and ‘fight your ground’ – plus any other idioms for survival you can come up with.

Survival in our family depended on being able to persuade, cajole, argue, explain, entertain, amuse, justify and coerce – all in language that was enriched and elaborated, expressive and nuanced, with passion, coherence, conviction and emotion, and with facial expression, gesture and body language to enhance and enrich the performance. In fact – YES you’re right – I had to learn to be an orator.

From the age of 6, ensuring my place and safety in our family of orators required oratory and I fought to retain that place. Those features I have listed as essential for my survival are the features of rhetoric – a passion of the ancient Greeks who also sought oratory and debate as their valued forms of entertainment.

Oracy is not oratory, but oratory is the ultimate form of oracy. It amused me when Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour candidate for Prime Minister, revealed himself to be a passionate advocate for oracy – even though he himself proved to be (in my opinion) the most boring of public speakers. Voice 21 initiated the establishment of the Oracy Education Commission in March 2024, and the report was published in November of the same year.

Amazingly, Keir Starmer appears to have had oracy coaching since the start of 2025 and is now proving to be an influential voice in the Trump Tariff Turmoil.

Meanwhile I am much enjoying myself speaking at events on the wonderful subject of oracy. There is so much to say, so much history, definition, explanation and modelling; and then the demonstration of oratory itself, with so much passion, perfection, coherence, conviction and charisma, so much emotion, exposition, empathy and energy.

The orator knows – without doubt – whether he or she has hit the mark and swept the audience along with the power of performance, the cheers and clapping, the laughter and gasps of horror will confirm that ‘the verbalisation of experience’ has conveyed the experience and enabled ‘the experience of verbalisation’ to quote the creator of the term ‘oracy’, Andrew Wilkinson.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Oracy? It's All Greek to Me

I am loving the work on oracy that has come my way since the rebirth in education of this amazing and powerful skill.

Who would have thought – when I left the ex-husband way back in late September of 1986 and returned to England after 17 years of teaching in the Caribbean – that my very first full-time teaching position would lead me to involvement with the original National Oracy Project of 1988 to 1993? I had obtained a post as Head of English at a large Bradford Middle School, and was thrilled to find that that school had registered to participate in this incredible initiative – the work of Andrew Wilkinson (lecturer and linguist at the University of Birmingham) who created the name ‘oracy’ in 1965 to re-promote the elaborated code of speech in schools and finally bring the power of talk into line with numeracy and literacy.

Basil Bernstein (linguist and researcher at London University: Institute of Education) had first advocated the teaching of elaborated code in all schools when his research revealed the great difference in achieving bench marks like learning to read and write for children who only spoke in the restricted code, when compared with those who spoke in the elaborated code all the time or who code switched with ease and impact between the two codes. He also demonstrated similar impact on examination results for older pupils at GCE (as it was then) and beyond.

Sadly, Wilkinson’s powerful relaunch had no more impact than Bernstein’s findings had had, as the original National Curriculum was launched in parallel – in 1987 – bringing great stress to the profession over those first years of the roll out and with its own version of Speaking and Listening being put on a par with reading and writing within the English Orders. Thus, the aspirations of Bernstein and Wilkinson to not only enable all children to become fluent and confident talkers, but also to enable them to code switch into the elaborated code of oratory whenever they so wished, were stifled in the Talk for Learning drive that underpinned the new curriculum.

The National Oracy Commission, led by Geoff Barton, has led to a rebirth of oracy and this opportunity must be seized and embraced in order to achieve that equality of opportunity and ability in the English language that we all aspire to and yet have failed thus far to achieve. If children can switch to a powerful oratory enriched with suave features, and delivered with confidence, coherence, passion and persuasion, they will not only empower themselves in daily discussion, debate and writing but they will also feel confidence to voice their opinions and knowledge in any forum before any audience. And all this whilst still talking in their daily lives in their natural family and cultural code of speech.

The great gift of rhetoric was first identified in ancient Greece and was recorded in parallel in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt and China. The language of rhetoric was later found in the first versions of The Bible. This powerful language form was a driving force in both Greek and Roman education from the 5th Century BC and continued to be a force taught to young people across Western Europe until the 18th Century, when it gradually declined in popularity and was absorbed by such educational trends as ‘elocution schools’. With a slow rebirth throughout the 20th Century, rhetoric played a more central role in the worlds of Western education for orators, lawyers, historians, statesmen and poets – mainly through the public school system and universities.

In all my reading and research into the history of oracy, however, I was never more excited than to find that the power of rhetoric is also identified in the animal kingdom amongst the more social animals. It has been identified in the song of birds, the danger warnings of some species, the trickery of chimpanzees and the courtship of deer. Whilst these are defined as predominantly rhetorical actions and body language, they are fundamentals that are shared by both humans and animals. Indeed – there are sections on body language, including facial expression and gesture, in my books on oracy both for teachers and for pupils. Who would have thought it? Perhaps when I finish my current book on oracy written directly to children, I should write a third one for other animals?

I am reliably informed that the study of animal rhetoric is known as ‘biorhetorics’ – perhaps a future project I would enjoy? Or should I leave things as they stand right now? A mystery of nature… It’s all Greek to me!

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

What are the Codes of Restricted and Elaborated Speech?

Codes of speech are the many different styles and forms of speech that people from around the English-speaking world use naturally and intuitively – or may be taught. They are often associated with specific locations across a country or different parts of the world, although some are generic and may be used alongside other codes. I quote:

Speech codes refer to the patterns of speech used by different social groups. These codes encompass vocabulary, syntax, and the underlying rules governing language use within a social context. (Easy Sociology, May 30th 2024)

The most commonly modelled and taught code of speech across England and the planet must be the agreed code of Standard English due to its priority in English education – and in reality this is a feature of speech that may be spoken in any accent as long as the speaker conforms to the rules of grammar, pronunciation and spelling in writing as agreed in the standardised form. This agreement was achieved over a period of almost 100 years in the second half of the fourteenth century and the early fifteenth century and became crucial in order to improve mutual understanding – which was growing increasingly difficult due to the many diverse dialects, patois and accents. It is essential for schools to teach Standard English – not to change the way children speak in their daily lives but so that they are able to write in Standard English and to read and understand it for wider communication purposes.

There are some who assume that Standard English also means elaborated speech or even Received Pronunciation – but whilst both of these codes are almost always in Standard English, the reverse is not applicable. Standard English may be simple in structure and vocabulary, and spoken within a local accent. I talk in my local Yorkshire accent (by choice as I commonly switch between four different codes) but I also follow the rules of Standard English except when I wish to exemplify dialect or a stronger accent.

Received Pronunciation (RP) is the correct name for what many of us – especially a Tyke like me – would call ‘posh’ talk. It’s the code of the aristocracy, royalty and many of the historically wealthy families – and is also commonly used by many in the world of academia. It involves the more affected pronunciation of crisp and elaborate English. You may hear that the speaker’s consonants throughout words are more clearly enunciated, and that inflexion and expression enrich the elaboration and conform with the expected norms of the more privileged in society.

However, elaborated speech may be used in other codes besides RP, including in all mild local accents, neutral accent and even sometimes within strong local accents in England. Our colleagues and friends in Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Republic, and Wales, as well as those in the USA, Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and others all speak English as their first language, each with their own unique accents, often with the elaborated code and in a mix of Standard and non-Standard English. Thus, the codes of English combine and blend to produce unique and colourful local speech.

Dialects are – for me – the most fascinating forms of speech in our country. They originated when communities grew and developed in isolation. Dialects are often unique to a locality. They have their own grammatical forms and some of the vocabulary is totally unique to that specific area. I will exemplify a Yorkshire dialect now:

Ayeup sithee, is’t thar ganging dahn’t ginnel Lass, ‘r is’t thar jus’ callin’ ower’t’wall awl’t deay?

Dialects do not conform to the rules of Standard English, so that many of the rules of grammar and of sentence structure may seem to be broken. Some vocabulary does not exist in Standard English and there is an increased use of contraction – often in ways that also do not conform. It is for these reasons – particularly the ‘short cuts’ of incomplete sentences and limited enrichment – that dialects are considered to represent the restricted code. Dialects do not use the elaborated code of enriched language, yet they are also unique and powerful, and of equal importance and significance as all other codes – they are just different.

Local accents are possibly the most frequently heard forms of speech for most of us as they are derived from former dialects that are softened, modified and conform to most or all of the rules of Standard English. I talk mainly in a Yorkshire local accent, not because it’s the only way I can talk but because I’m proud of my culture and my heritage. When us is using a broader local accent, yer’ll ‘ear some dropping uv letters like ‘t’s an’ ‘h’s an’ d’s, an’ some grammatical forms of verbs is not quite right. You might hear us say things like ‘he were’ or ‘they is’ or ‘we’s gone’. In the main, however, the language is in Standard English and children learn how to correct their spoken deviations in school as their writing prowess develops.

Two codes of speech that have historically remained the province of particular strata of the English-speaking population are the elaborated code and the restricted code. As the world of education turns its attention to Sir Keir Starmer’s cry for a focus on oracy, understanding of these two codes becomes increasingly important.

The elaborated code of speech has been in existence since civilisation developed – the Greeks were particularly known for their passion for rhetoric. Collins Dictionary defines rhetoric as:

- the study of the technique of using language effectively ·

- the art of using speech to persuade, influence, or please; …

This is a reasonable definition of oracy, at a time when we search to define this ‘new’ code of speech. For the Greeks, rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, initially developed to persuade. Greek society relied on oral expression, which also included the ability to inform and give speeches of praise, known then as epideictic (to praise or blame someone) speeches. (Lumen: Principles of Public Speaking)

The following words of Aristotle are extremely appropriate as a structure for working with children on developing the skills of oratory, and for best impact the language must be elaborated:

In making a speech one must study three points: first, the means of producing persuasion; second, the language; third, the proper arrangement of the various parts of the speech. – Aristotle

Lumen lists the Key Features of elaborated speech as:

- Explicitness: Speakers using elaborated codes articulate their meanings clearly, providing detailed explanations and justifications for their statements.

- Flexibility: This code allows for flexibility in language use, enabling speakers to adapt their speech to various contexts and audiences.

- Abstract Concepts: Elaborated codes often involve abstract concepts and hypothetical reasoning, which are essential for academic and professional discourse.

I feel that these features should explicitly include the features of language found, such as sophisticated sentence structures, suave vocabulary and rhetorical language, that are so much a part of it. The internet defines elaborated code in the following way:

Elaborated code refers to the language used in formal situations. Teachers, textbooks, and exam papers use this kind of language. It is characterised by its use of a wide range of vocabulary, complex sentence structures, and precise grammatical conventions.

From a teaching perspective, I feel that this description is extremely useful. Basil Bernstein (1924 to 2000) was a linguist and researcher in The Institute for Education at The University of London and he led important research that showed that having the ability to talk fluently in the elaborated code led to children learning to read and write earlier and to achieve more highly in examinations. This may have been the first use of the term ‘elaborated’.

Bernstein’s findings also showed that children only able to speak in the restricted code were severely disadvantaged in terms of academic progress and achievement, and he recommended that all children should be taught this code in school.

At the time of Bernstein’s research, the majority of children who were able to speak fluently and confidently in the elaborated code were those who had learnt it from their parents and family whilst growing up in the home, and these were children with an articulate parent or parents who already spoke in elaborated code. Public schools and some private schools also taught the elaborated code pro-actively to enhance performance and to enable rhetoric for debate. Children from homes where they only heard the restricted code most of the time, were usually only able to speak in that code.

The restricted speech code is characterised by its reliance on context-bound language. It uses a limited vocabulary and simpler sentence structures, with meanings often inferred from the immediate social context. Patois, dialects and strong local accents are all often confined entirely to a restricted code.

Sentences are mainly incomplete and abbreviated. Speech does not conform to the rules of Standard English and some vocabulary is unique to the dialect. Few state schools have ever taught the elaborated code and thus children who only speak in it remained severely disadvantaged.

Andrew Wilkinson started his career as a teacher and thus he identified fully with the findings of Bernstein. In the early 1960s he became a lecturer, linguist and researcher at the University of Birmingham. He took up the cause of teaching the elaborated code, which he named ‘oracy’, in 1965. Wilkinson created this name to raise the profile of the code and to give it equal status with literacy and numeracy in the curriculum. He strongly advocated that oracy was not to be taught to make all children change their daily speech, but was to be a code they had at their fingertips should they choose to use it.

Thus it is that the world of education is now listening to the plea from the Prime Minister – despite the fact that he, himself, is a somewhat lack-lustre speaker. At his behest, the Oracy Commission is working hard – under the leadership of the esteemed Geoff Barton – to provide a clear definition and guidelines to empower all schools to teach this vital additional code, not in order to change the way our pupils speak but in order to empower them to code switch into elaborated code if and when the time is appropriate and if they choose to.

May I close by reminding us all that all codes of speech are of equal importance and value, and the speaker must retain the right to use their natural code or a code of their choice in their daily life without fear of ridicule or judgement. No one code is better than the others – they are all different and are useful for different reasons. I choose to continue to speak in my Yorkshire accent, despite the fact that I was raised in a neutral code with elaborated speech and with the ability to switch naturally into RP when I desire to.

Ah’m Yorkshire an’ ah’m proud o’t!

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Reflections on the Oracy Education Commission Report

This is long for a blog but it felt essential to include some of the highly significant quotes found throughout the report.

The Oracy Education Commission Report was released on Tuesday 8th October to a wide and eagerly awaiting audience. Many schools and senior leaders are still growing and developing their understanding of what oracy actually is and the implications for future teaching and classroom practice. Many consultants, like myself, and presumably also many academics, were wondering whether the findings of the commission would support or conflict with already formed opinions and recommendations. We need not have worried. The report is a liberal summation of the opinions and findings of the majority and there is little to conflict or negate authentic existing practice.

There are, however, just three areas I would appreciate further clarification and possibly exploration around. They are the matters of the definition of:

- What is oracy?

- Why should oracy be actually taught pro-actively in schools?

- How should that be done for the best outcomes for children?

The answers to these questions will then inform the decisions and future actions of teacher trainers and school leaders as they move forward to address this sensitive but vital inclusion in the curriculum – the fourth R!

Let me open by listing the many aspects of the report that I found particularly encouraging, reassuring or even exciting, and express the few concerns I have as I go along.

A huge strength of the report is the frequent inclusion of the words of actual teaching practitioners on many levels, and – for me in my work – the thoroughness and creativity with which so many primary practitioners are empowering pupils in the gift of choice is both moving and humbling. As teachers, it is not our job to challenge the opinions of linguists, but many of us do keep abreast with the world of academia to strengthen our beliefs and for confirmation and justification. I particularly valued:

Oracy education should [..include] learning about talk, particularly the sociolinguistics of code-switching, to raise awareness of the validity of effective communication in multiple spoken Englishes. THE ENGLISH ASSOCIATION, WRITTEN EVIDENCE TO THE COMMISSION (P18)

I loved the statement at the opening of the report that:

There is very strong evidence that oracy education helps children in learning to, through and about talk, listening and communication. (P5)

This is not, in itself, a definition but is rather a statement of fact that justifies the opinion that oracy must become the fourth R, on a parallel with reading, writing and arithmetic. On pages 14 and 28, the report provides its definition of oracy saying that:

Oracy is: articulating ideas, developing understanding and engaging with others through speaking, listening and communication.

My personal research and opinions remain that oracy is this and so much more than this – and also so much less! The report appears to define oracy as the general aim of talk and communication rather than as a specific – that is the process towards oration and oratory. It identifies, in the need for change:

To realise the promise of oracy education, we need to adopt a shared definition and common understanding of what oracy is, and where to locate it in our education ecosystem. (P18)

I do so agree with this and feel there is more work to do in this area as we are not quite there yet.

The quoting of Sir Robin Alexander, whose inspirational work on dialogic teaching failed to create the impact and change that it deserved, which would have seen the initiation of the implementation of oracy through an alternative approach, was pleasing.

Dialogic teaching is a ‘pedagogy of the spoken word which harnesses the power of talk to stimulate and extend students’ thinking, learning, knowing and understanding, and to enable them to discuss, reason and argue. (P15)

Oracy also aspires to ‘harness the power of talk’ to inspire, excite, convey and convince through the passion of communication. This exciting process could benefit from a definition that is slightly more than speaking and listening.

The report goes on to say that:

The study of speech and debate (perhaps through the study of rhetoric) is a key aspect of oracy education. Complementing their subject-led learning, these practices help students to explore the relationship between persuasion, argumentation and evidence. They learn how arguments can be evaluated in relation to reason; knowledge or fact; and community or audience. As such, speech and debate provide opportunities for students to develop critical thinking and reasoning skills that are of benefit across all curricular learning, and to active citizenship both at school and in later life. (P15)

Here, the report is surely describing a process that includes but is so much more than:

articulating ideas, developing understanding and engaging with others through speaking, listening and communication

Indeed, all the modes of talk listed on page 32 can be pursued equally effectively as both plain talk or as oratory.

I very much agree with the immediate acknowledgement at the opening of the report that the effectiveness of oracy must start from talk, the acknowledgement that the impact of teaching and developing language skills – ideally from birth in the home but this has proved to be sadly not always the case – and thus it is essential from a very young age and/or as soon as children enter the Early Years of education. It says:

we believe that alongside reading, writing and arithmetic, oracy is the fourth ‘R’: an essential, foundational building block to support our young people on their journey towards living fulfilling adult lives. (P5)

I did, however, find there is still a little confusion as to whether this crucial early development of talk and listening skills is actually the first stage of oracy or an essential preliminary other.

On page 7 the report states:

We know that oracy education is not a panacea that can address all the challenges experienced by our children and young people or the weaknesses of our education system. It is neither a quick-fix, nor an intervention that can simply be added as an appendage to the prevailing ways of educating our children and young people.

Yet it also states emphatically that oracy does enable additional informed choices that can change people’s lives. I very much, therefore, appreciated the quotation from Barbara Bleiman, (2024):

Studying spoken language can empower students to make informed choices about their language and communication and understand the impact of these choices. It can also help them analyse and appraise the speech choices of others. (P14)

Children and young people should learn about listeners’ perceptions and consider how race, class, and other speaker characteristics influence what we hear and why. (P15)

The key word, for me, when working in this area is ‘choice’. If pupils are not taught the codes of language, about language and about the purposes of codes of language they are not empowered to make choices. Pupils move through school intuitively code switching for purpose and impact, but if there is a code that they are denied access to for fear of bigotry or discrimination or judgemental behaviour, their choices and resulting opportunities – especially in adulthood – may be seriously limited.

The opening paragraph on page 20 may illustrate the difficulties of summing up a complex process in a brief definition. It could be read as indicating a difference between talk per se and oracy, when it says ‘Oracy is also a …’:

Talk is a feature of every classroom and educational setting. Harnessed effectively for learning, it enhances cognition and improves outcomes. Oracy is also a curricular object and educational end itself. It can be nurtured, taught, demonstrated and applied through explicit instruction, planned authentic learning experiences, as well as teachable moments.

Yet rereading suggests it could purely be using ‘also’ as a further qualifier rather than as an addition. The final findings of the paragraph advocate embedding oracy from ‘the earliest stage’, but many teachers would advise that the job of teaching talk, the purposes of talk, learning to talk and through talk and to listen to and absorb the talk of others – responding and learning from it appropriately – are huge targets in their own right and involve many hours of planned, quality discourse throughout and across the curriculum from the moment of entry to education. Is oracy simply a progression on this journey of talk? In which case why give it a new title and more importance than the other stages? Or is it an extension in its own right? In which case must its definition be more specific to inform effective planning, preparation and implementation?

It was inevitable that the old chestnut, ‘Standard English’, would be obliged to raise its head once more. We are all aware that Standard English is no more than one of the many codes of speech found in English and that it is no better or worse than any other code, however it is the agreed code for public communication and publication and as such it is extremely important that pupils should have the choice of deploying it.

It is important to remember that speaking in Standard English is not the same as speaking with Received Pronunciation (‘talking posh’). Standard English purely means speaking with the agreed standard form of grammar and pronunciation. Speaking with an accent doesn’t mean you are not speaking or can not speak Standard English.

The purpose of teaching Standard English in primary schools is to enable pupils to write in Standard English when required. The premise that teaching children to speak in Standard English for purpose is not the way to ensure children can then write in Standard English, is flawed. If the child can say it, the child can write it – providing speech and writing are part of their portfolio of skills. In nearly sixty years of teaching and advising I have never found a more effective way to teach language constructions than through talk – and I have always worked hard to ensure I trial fairly every new hypothesis put forward. Use of qualifiers such as ‘sometimes’ and ‘in some cases’ when mentioning bad practice (P45) does not justify a failure to empower those who will not receive this gift of choice naturally, providing this is done in a culture of embracing and respecting all codes of speech. Using the bad practice of a few is not justification for refusal to teach an important aspect of the curriculum. If it were, very little would be taught. I felt that re-introducing the right to choice here would have brought balance to the perspective.

I opened by stating that there were three areas I would appreciate further clarification and possibly exploration around.

- What is oracy? I believe the answer is that it is both a progression and an appendix to talk and as such it requires informed pro-active teaching.

- Why should oracy be actually taught pro-actively in schools? Because children everywhere have the right to be given the full range of codes of speech to enable present and future choices that will empower and enable success. Most codes are learnt naturally through life experience, but for many children exposure to both oratory and Standard English are not natural and will only be acquired through planned and informed classroom activity.

- How should this be done to achieve the best outcomes for children? Through regular – and when necessary repetitive – teaching and application of skills within and across learning, preferably in enjoyable and stimulating contexts. There are many interesting and helpful quotations of good practice within subjects and contexts throughout the report, and yet every one of these applies elements of oracy to a particular subject that could – in reality – be applied universally in every subject and context with skillful planning.

The final paragraph on ‘What needs to change’ states:

Children should be taught to explore their language choices and make conscious, informed decisions about how to communicate effectively in different contexts. As a result, the oracy components of a revised National Curriculum should emphasise the value of different dialects and ways of communicating and avoid placing undue emphasis on ‘standard English’ or ‘fluency.’ The aim of learning to talk, listen and communicate should be to support all young people to increase their repertoire of speaking, listening and communication skills, rather than to adopt one particular form of spoken language. (P47)

Perhaps this excellent ending to a thorough and comprehensive report could acknowledge that the role of the teacher when addressing language is to cross those boundaries between speech and writing, emphasising the need for confident conscious use of Standard English when required, at the same time as valuing and celebrating all personal codes of speech deployed for purpose. The report correctly acknowledges that many children enter school with little or no grasp of Standard English, which remains an essential for future success. This must also be one of the codes in a pupil’s repertoire of choices for purpose and as such, must continue to be taught in schools.

When the Oracy Commission’s report is accepted into practice, I sincerely hope that the answers to these questions and dichotomies will have been clarified and agreed so that they may then inform the decisions and future actions of teacher trainers and school leaders as they move forward to address this sensitive but vital extension of the curriculum – the fourth R!

In the meantime, warmest congratulations to Geoff Barton and the Commission for an outstanding piece of potential oratory; for all the hours of hard work, conversations, thought, effort and decisions committed to present so comprehensive a document. May it be the forerunner of greatly increased clarity and vision that leads the world of education and the population of the future to effective lasting change.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

The Birth of a New Book

Order Oracy Is Not Just Speaking and Listening.

It really is like a birthday when the first copies of your new book arrive! On August 29th we celebrated a birthday – in a very large cardboard box.

‘Oracy is Not Just Speaking and Listening’ was conceived in April 2024 and written between June and September. It was not hard to write as I had researched and generated almost all the content over the previous year or more in the context of my work supporting schools and organisations.

Natural birth is always painful without intervention by others. It is the culmination of a period of preparation, growth and development that is enhanced – usually – by anticipation and some excitement. The last weeks, however, may be very painful with constant monitoring, checking, proofing, reading and re-reading, editing and worrying until at last someone has to say ‘enough is enough’ – let’s do this thing. Then we commit…

I am so fortunate in the colleague I work with when publishing. Richard is calm, focused and with an eye as sharp as a razor in the final proofing stages. This is important because – although I am a very effective proof reader – all who write will tell you that you can’t proof your own work without something slipping past you. Even with three thorough reads by each of us, Talk:Write still has one very small slip in it which I only spotted very recently. Has anyone else found it yet?

This latest book is not intended as an academic tome or an anthology of research, although it does contain sufficient information about the roots of the term ‘oracy’ to justify the interpretation of this terminology as closely as possible to the way Andrew Wilkinson intended when he created the concept in 1965 and also to the later research of others, including Rupert Knight. The confusion of interpretations, definitions and opinions that exist today will hopefully be resolved by the National Oracy Commission when their work is done. Geoff Barton is a great thinker and leader. I look forward to the commission’s findings with interest. In the meantime, I am confident that the interpretation of ‘oracy’ portrayed in this book is as close to the original intention of the creator as is possible.

Besides de-mystifying the term ‘oracy’ however, the new book provides clear strategies and guidance for effective launch of oracy in a school. This includes ways to make it enjoyable and even fun whilst ensuring that all codes of speech are respected and protected. Our aim is not to change children’s daily speech, but rather to empower them to make choices about how they speak in different situations. The choices they make and the situations they choose to deploy them in are down to the children themselves. My aim is to see pupils enter the adult world of employment and enterprise as individuals with choices, and when they feel the time and situation is right – adults who are empowered to switch smoothly and naturally into powerful oratory that is passionate, persuasive, emotive, informed and detailed.

But when that birthday box is opened, and we first see the product – the fruits of our labour – aims and aspirations are forgotten. It is a moment of pure excitement that focuses solely on the product. And what a moment that was! What a cover and graphics! What simple and effective layout. I love it and I hope that all of you who have already bought it will love it too.

Thank you to you all, Ros

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

School Speak Oracy

I was sent a link to an ongoing discussion on Twitter about the ethics of teaching children who do not speak in Standard English to do so. There are clearly many people who feel great sensitivity around this area – and that is totally understandable.

One of the schools I work most closely with is in an area of massive deprivation, with almost the entire pupil body speaking either in strong Yorkshire accents or with cultural ones. Their teachers and support staff, most of whom also speak with regional accents (although less than half the teachers are from Yorkshire, while all the support staff are from the locality of the school) have embraced the necessities of children learning to speak in the standardised form of English. They have long used my maxim: ‘If a child can’t say it, a child can’t write it,’ and this is now modified to:

‘If a child can’t say it in Standard English, a child can’t write it in Standard English.’

Children must learn to speak confidently and articulately in Standard English if they are to think in the standard form and therefore write, proof and edit in it, but this does NOT mean that they can no longer enjoy and celebrate their own local accent.

The risk of offence or humiliation for children in learning Standard English is not the ‘what’ but the ‘how’. By including the standardised form of English as one of the ‘codes of speech’ pupils will hear around them in their lives – whether in shops, in restaurants, on streets, on transport, on television or on other media – and teaching children to respect all these forms of speech, the stigmas are removed and the elitism is eradicated. We then teach them to switch easily between forms (this is called code switching) whilst having fun – often through role play and performance – and with practice this becomes a smooth transition from their own home accent into other forms of their choice for purpose, but always including models that are entirely in Standard English.

Sadly, some in the profession have not yet understood that Standard English may still be spoken with a regional accent – it purely means that all grammar and pronunciation will be accurate. Where alternative grammatical and vocabulary forms exist that are not in the accepted standard form, speech becomes a dialect (again, a wonderful thing to be celebrated. I love Yorkshire dialects).

Included in the children’s increased repertoire of readily-available forms of speech, however, will also be ‘received pronunciation’ – or the accent of many of the highly educated or the wealthy – formerly known as ‘BBC English’. This is treated purely as another code of speech in their repertoire, and children will use it in role play, drama and presentations in the same way as they will use other codes. We have renamed this code ‘School Speak’ in our oracy programme, and encourage schools to modify that to the name of the school (for example, Roundwood Speak) if they so choose.

Thus, we make ‘School Speak’ an inclusive form that every child and adult in the school will use when asked – whether as the sustained form of speech for all throughout one or more entire lessons a day, or for specific purposes such as a debate, a performance (for example, of poetry) or as a particular character in role play. ALL children sharing the same speech form for the same purposes at the same time… equality with mutual respect – and then all children reverting to the daily speech code of their choice… again, equality with mutual respect!

I have just enjoyed writing a short book for publication as a PDF to help schools to launch and support development of powerful oratory in their schools with dignity. This very affordable book will include resources to support teachers and pupils in developing their exciting and highly entertaining orations for school gatherings and celebrations. More information will be available on our website soon.

Through this means of embedding School Speak in fun and dramatic performances, children will find, as time progresses, that switching from their daily voice, local accent or ‘street talk’ into an impressive form of oratory when appropriate, to be a natural and rewarding experience that will support them in their life as they represent their class, their school and their family, as they attend interviews and as they interact with people of other speech forms in the wider world.

There is no shame in this achievement – only joy and celebration of choice and flexibility. Where else will children develop this empowering and life-changing skill? The clue is in the name – ‘teachers’. We are the teachers, we should empower and enable without being made to feel shame or derision.

Only a week or so ago, a secondary teacher tweeted explaining how he modelled speaking in modified standard English, using sophisticated features and in expressive tones of respect and oration when speaking to all his students in school, and how so many were beginning to reply in a similar vein, modifying their local ‘street talk’ without the need for judgmental comment or potentially humiliating teaching. I wonder, sometimes, whether all our secondary colleagues – who we value so highly – are aware of how hard we work to prepare our pupils for secondary education?

We TEACH them…

…and so often a challenging aspect of learning in one phase of education later becomes a revisit – reawakening memories that are deep seated in the sub-conscious and enabling them to be refreshed, extended and invigorated with the maturity of the years and giving the impression of an ease of learning that belies the hard work of the previous phases.

Never feel shame about teaching children something that could potentially enrich and reform their life opportunities, for we all know that TEACHERS MAKE THE DIFFERENCE.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Oracy Is Not Just Speaking and Listening

I visit schools who are doing ‘oracy’ and I see speaking and listening! Mind you – I am so pleased to see children conversing and teachers asking a wealth of interesting questions – but it ain’t oracy. Speaking and listening is valuable; oracy is valuable – they overlap and have elements in common – but they are different. It remains confusing because, inevitably, you see and hear one in the other and vice versa and often the boundaries are very blurred.

So, what IS oracy and how do I know what it isn’t when so many great teachers and leaders think they are ‘doing’ it? Well, to be fair it has taken me over two years and a lot of hard work to come up with an answer that may solve that mystery.

You see, Andrew Wilkinson did not know the answer himself when he came up with the terminology in 1965. How can you create a new ‘something’ to teach children when you do not yet know what the ‘something’ is? It is important to be able to define your vision before you attempt to communicate it to others. That is why new thinking and new ideas often have slow and shaky starts until the definition is crystal.

Wilkinson’s aspiration was good, however, he wanted to raise the profile of talk and language so that it was NOT just speaking and listening. He created the name ‘oracy’ to put his new aspiration on a par with numeracy and literacy and he developed a massive and much underrated national initiative to promote it, but he still didn’t know what it was and neither did most of the country.

There is so much written about the cruciality of oracy, and I have read much of it, but nowhere do you truly understand what it means. Voice 21 has established itself as an authority, saying;

We believe that schools have the power to change a child’s life and create a fairer society. We support schools to build oracy into learning, the curriculum and wider school life. Oracy is the ability to speak and listen in a range of different contexts – one-to-one, in groups and to a larger audience. Oracy skills set children up for success in school and life.

So what is it? Well, perhaps Voice 21 is close to defining ‘oracy’ when it tells you what you will see and hear in schools they work with:

In Voice 21 schools, you will hear students solving problems collaboratively in maths and dissecting arguments in history, talking through conflicts in the playground and leading assemblies.

So close to a definition – but not! Was Andrew Wilkinson influenced by Sir Evelyn Wrench when the latter said that effective discussion and communication had four components:

- reasoning and evidence;

- organisation and presentation;

- listening and response;

- expression and delivery.

Wrench, a former journalist, had seen his original international communication organisations morph into the promotion of discussion and communication between young people around the world in order that they might better understand each other and show mutual respect by the mid-1960s, before he died.

Wrench (1882 to 1966) saw international co-operation and communication as crucial for world peace and his summary of the four components for his aspirations possibly reflect the aims of Voice 21:

Voice 21 sets out four strands of oracy – Physical, Linguistic, Cognitive and Social and Emotional. The ‘physical’ includes elements such as voice projection, using eye contact and gesture. ‘Linguistic’ involves using appropriate vocabulary and choosing the right language for different occasions; ‘cognitive’ is about organising the content of your speech and ‘social and emotional ’ includes working with others, taking turns and developing confidence in speaking.

Ah, now it is becoming clearer. In identifying the four components of communication promoted through his work, he was embracing the best of speaking and listening – a best that verges on oracy and sometimes becomes it.

Wilkinson’s aspirations for the National Oracy Project (1987 to 1993) were established as a key contribution to the early National Curriculum. However, Wilkinson himself struggled to define the term – eventually coming up with a statement he immediately felt was inadequate for the job. In his own words, Wilkinson said that oracy was;

…the verbalisation of experience.

As he promptly acknowledged his dissatisfaction with this, a colleague suggested that perhaps it was rather;

…the experience of verbalisation…

whereupon Wilkinson seized the diametric and married the two. I read them, I understood them, but I knew not what they meant.

I was extremely fortunate to be invited to participate in the Bradford strand of the National Oracy Project upon my return to the United Kingdom in 1986 after 17 years in the Caribbean. I had no training, no induction or introduction, no materials and attended no meetings but I much enjoyed working with my 13-year-old Middle School pupils on communication skills and we all developed a passion for the huge effectiveness of talk, debate and discussion on our studies. We ‘did’ speaking and listening in the best sense of the word. We talked endlessly about the power of talk and the role inspirational discussion plays in understanding learning, clarifying it, embedding it and moving it forward.

We benefit so hugely from the first three elements of Wrench’s description, but we do not often – in the busy overloaded world of education in England – move through to that final stage…

For the past two years I have studied, reflected on and written about oracy, and finally I feel my understanding reflects Wilkinson’s diametric. I have watched communication and discussion radically improve in the schools participating in our trials, but the key element is still in development. And then – while enjoying a dramatic performance of a verbalisation of the experience of analysing a response to a mythical image – the penny dropped as the missing word fell into place.

It is an oral performance of an experience, performed with passion and dramatic communication. It takes creativity, skill, rehearsal and interpretation… but oh it is so powerful in its illustration and conveyance of the impact of an experience that must have been 100% understood, absorbed and embraced to be verbalised through oracy.

It is exciting to be on the fringes of the birth of the Oracy Commission:

The Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England is an independent commission, chaired by Geoff Barton and hosted by Voice 21.

I see with interest that their discussions and contributions follow that same pathway that I have been struggling along with so much joy and enlightenment. Now I have words to express what I was fortunate to have been given by an articulate and inquisitive family at the kitchen table in the days before TV and media – an ability used all my career without ever knowing how to define it. This was not a gift of class but rather a gift of culture. We were genuinely impoverished financially but blessed in ability to use language. Now every child in the country and the world may have the great good fortune to acquire those same skills.

Of course I was unable to define oracy, I was still in the understanding and absorbing phase – as so many others are still today. It is everything both Welch and Wilkinson said and everything Voice 21 has said. You can’t achieve oracy without speaking and listening but you can usefully and productively use speaking and listening in education without taking it on that final, massive-for-many climb into oracy.

Now we know it, let’s get our boots on…

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Technical Grammar in Primary

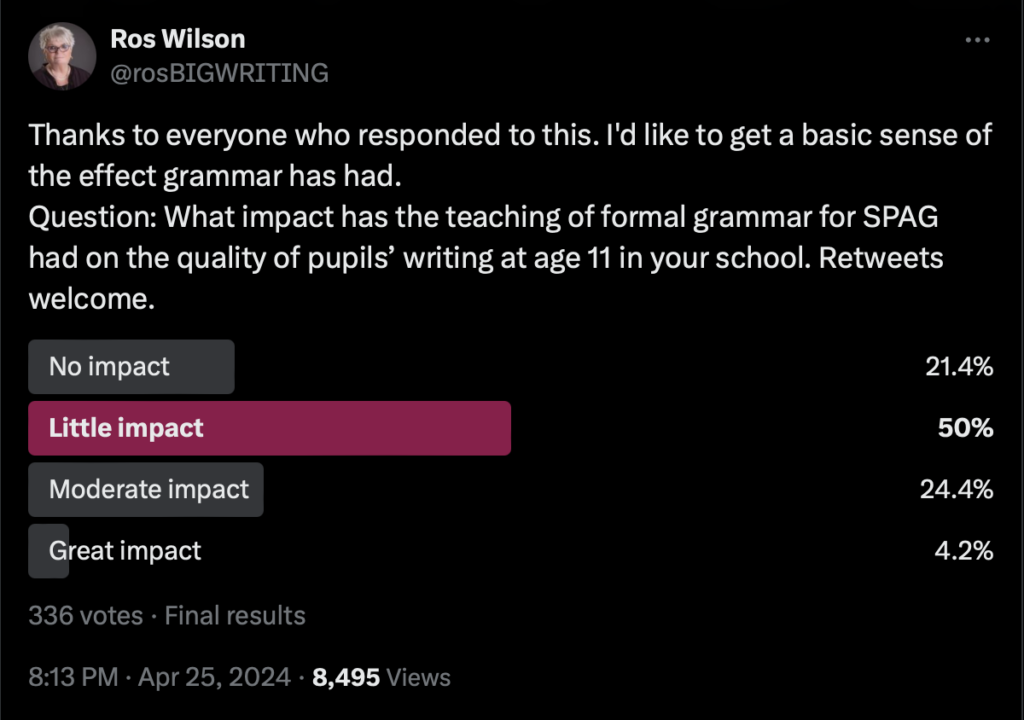

I recently started a Twitter debate about the merits and disadvantages of the formal teaching of technical terminology for grammar. The consensus seemed to be that the only advantages for the teaching of primary aged children were if a school wanted children to perform well in the SPAG tests in Year 6! As ever, there was some advocacy for the benefits for MFL teaching in secondary schools – however, the majority of primary school leaders do not seem to see preparing pupils for success in secondary MFL exams as a priority for primary education.

Over 70% of the colleagues who responded to the poll we circulated on teaching myriad technical grammatical terminology that was included (by statutory requirement) in the revised National Curriculum of 2014 – without consultation – concluded that it had little or no impact on pupils’ writing prowess in Year 6. Indeed, a significant number of comments indicated that writing had lost a lot of its zest and had become more of a technical chore. Over 20% of respondents thought the benefits were minimal to none. One comment noted improvement to understanding rules of punctuation and the others related to later benefits in secondary education.

If children already have a good understanding of more complex grammatical structures and are able to use them effectively in their writing, then the later learning of the formal terminology is made easier and has purpose and meaning. The problem with the grammar requirements imposed is that they require the formal teaching first and then the later explanation of what it means and why a writer might need it. It reminds me strongly of the textbooks we used for learning grammar when I was at secondary school back in the 1950s.

Thinking of these led me to google grammar textbooks of the 1950s and to my surprise the search picked up on grammar today, and the first items identified were all blogs or similar by esteemed writers or educators criticising the imposition of the technical grammar for SPAG.

Michael Rosen’s blog of March 2016 makes protest about the introduction of SPAG. He provides a sample 11 plus paper from that era and says:

You can see what kind of ‘grammar’ questions we had in the 11 plus exams in the 1950s here. It was limited, as I have said, mostly to using the simplest terms – noun, verb, adjective, adverb… and the simplest stuff on tense. The questions mostly involved ‘filling in the gap’ type, so at least you had the context of that sentence to get it right. I’m not saying that this was ideal either, but it was fairly limited in terms of the amount of time we spent doing it and how much emphasis there was on doing it.

Even so, this was part of the means by which the 1950s system failed at least two-thirds of all children. It is quite unfair of Nick Gibb to claim that this is what’s being ‘brought back’. A much more complex raft of terms and processes are in SPaG and it’s one of the main means by which schools and teachers are being judged.

In ‘The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar’, Rachel Cleary (The Atlantic, 2002) says:

A century of research shows that traditional grammar lessons – those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech – don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers. Yes, they need to learn grammar, but the old-fashioned way does not work. This finding – confirmed in 1984, 2007, and 2012 through reviews of over 250 studies – is consistent among students of all ages, from elementary school through college. For example, one well-regarded study followed three groups of students from 9th to 11th grade where one group had traditional rule-bound lessons, a second received an alternative approach to grammar instruction, and a third received no grammar lessons at all, just more literature and creative writing. The result: No significant differences among the three groups – except that both grammar groups emerged with a strong antipathy to English.

And Rachel was discussing the impact of formal grammar in secondary schools.

In a desperate urge to be democratic and quote both sides of the argument I then put ‘support for teaching technical grammar at primary school’ into the search engine and the following came up: Teaching Technical Grammar Terms Doesn’t Improve Children’s Writing (Dominic Wyse, Teachwire, 2024). Dominic says:

We now have the benefit of a significant amount of research to inform the ways in which writing can, and perhaps should, be taught. I have recently contributed to this research in two ways. Firstly, I’ve undertaken an analysis of the research evidence on whether the teaching of formal grammar helps writing. Secondly, I’ve also undertaken a four-year study of writing from a range of perspectives including philosophical, historical and empirical research studies addressing writing across the life course… In addition to more than 150 individually specified elements of spelling and five pages of detailed specification of grammar (that are statutory), primary teachers in England are required to teach and assess their pupils’ knowledge of a range of terms, including compounds, suffixes, determiners, cohesion, ambiguity, ellipsis, modal verbs and lots more. It is presumably intended that the learning of these terms will help children to write better because they are included in the programme of study for writing, yet the evidence is clear – traditional grammar teaching does not lead to improvements in children’s writing.

All in all, articles and blogs critical of the NC 2014 grammar requirements far outweigh support for the arbitrary decisions of the then non-educationalist Secretary of State for education and confirm my despair that a succession of changes of leadership has failed to address the lack of judgement in the English curriculum criticised by so many. The degree of detail required by the inclusion of technical terminology for grammar in the 2014 NC is absolutely unnecessary for effective writing by pupils up to fourteen years old and has no impact on communication, creativity or composition. This level of learning is only necessary for those seeking higher level qualifications in the area of linguistics.

I conclude this blog with the wisdom of Simon Kidwell, President NAHT, in his blog, published by Teachwire in 2022:

Since 2014 I have spoken to a senior politician at the DfE and to experts in the field of teaching grammar, and I am yet to meet anyone who believes that the current grammar curriculum for primary schools is fit for purpose or age-appropriate. One teacher, Alison Vaughan, commented: “The overloaded grammar curriculum holds back learning for those with poor working memory and slow processing. These students are already working hard to remember punctuation and spelling… They need more time consolidating the basics, not complex terminology.” My colleague, headteacher Michael Tidd, added: “I think some of it is just pointless at primary level (I’m looking at you, subjunctive form!) and ends up being overly simplistic because of that…” Objections extend beyond the classroom, too, with The Times reporting that the government’s key curriculum adviser, Tim Oates, said that there was a “genuine problem about undue complexity in demand” in the content of 2016’s SPaG test. A lot of the issue, then, is with curricular sequencing, or a lack thereof. The teaching timeline for these complex concepts is out of whack, and we need to reconsider at what point we should be expecting our pupils to understand and absorb them.

Simon Kidwell has worked as a headteacher and school principal for 17 years, and has led three successful primary schools to achieve rapid and sustained improvement.

It is distressing to see political leaders, who appear to be totally lacking in knowledge or understanding about the needs and abilities of pupils in primary education, ignore the wealth of knowledge and opinion expressed by primary leaders and experts. If, as Simon Kidwell intimates, the NAHT is ready and able to take the lead in decision making for education, we may at last see curricular reform that reflects the true principles of education for our pupils. Simon closed the powerful 2024 NAHT Conference with the words; “The solutions to the challenges we have exist in this room.” May our talented heads rise to those challenges and bring stability and strength back to our profession.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Reflections on It Takes 5 Years to Become a Teacher

It is now 4 years since we published ‘It Takes 5 Years to Become a Teacher’, and it is gratifying how popular this little book has become. Besides the main body of my personal biographical experience and myriad advice and tips, there are a significant number of case studies full of the early days of a range of colleagues from all over the country and the world.

Recently, I have so enjoyed dipping back into these case studies, savouring the rich mix of experiences from the first years in the classroom and amusing tales of blunders and mini disasters that never fail to make me chuckle. I shall always be grateful for the plethora of colleagues who so generously contributed their memories of those first years in the profession.

What the writing and compilation of this book shows so clearly is that no amount of university study and brief placement experience can prepare us for the totally unexpected and unpredictable mishaps and moments of bliss that working with children brings. It is that very unpredictability that makes no amount of training, coaching and study able to prevent or adequately prepare us for. Many of us – seemingly well prepared and geared up for this new adventure – found the first weeks ran smoothly with compliant pupils and sweet successes – and then the trials began. Small difficulties and unexpected glitches began to confront us and exposed our naivety, tempting some pupils to test us and seize the opportunity to amuse their peers with antics of a class clown. The worst events, however, were often those that were purely the outcome of our own lack of experience and thus slow or inappropriate reactions.

Teaching is a wonderful career, diverse and different from minute to minute. It is hard to think of another profession where, for six hours a day (seven, but with two short breaks), an individual is unable to sit down and relax, sip a coffee or a coke, nibble a biscuit or suck a sweet or make or answer a quick phone call. Other professions that handle life can snatch a couple of minutes between cases – but not teachers. Save for a short toilet stop at morning play and an average of 20 minutes of the 45 to 60 minute lunch break, we are constantly vigilant, orating, articulating, chattering, conversing, discussing, echoing, enunciating, expressing, pronouncing, ranting, repeating and generally performing – dynamic, dramatic and vigorous.

We are thespians, scientists, astronomers, explorers, researchers and debaters. Does any other profession that is not on the stage wear so many cloaks? Adopt so many roles? It is our privilege to interest and engage, to motivate and excite, to charm and persuade, often with charisma and wit – even when we are exhausted, under the weather or in the midst of some personal crisis in our private life.

Rereading this summary of features of life for those of us with the privilege of working daily in the classroom, I wonder how we do it and how we sustain it day in and day out, in all weathers and throughout all the normal traumas life brings – and particularly how we did it as young and innocent newcomers to the profession. No wonder there were times when we struggled, times when we questioned our abilities and our commitment. And then there was the ever-increasing mountain of paperwork, most of which has no bearing on our daily ability to teach effectively; much of it imposed by those who have never experienced this career we have chosen and have no in-depth knowledge of what we go through day in and day out.

Yet we survive, we battle on and slowly the sun rises and all falls into place and clarity dawns. We are never safe from the unexpected, but our competency to cope and to lift our heads and deal with the day-to-day crises and chaos with confidence and clarity grows and blossoms as we truly become effective and efficient teachers. So, have faith, learn to laugh at yourself and talk endlessly with trusted colleagues, family and friends as you find your way, blossom and grow.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.