Technical Grammar in Primary

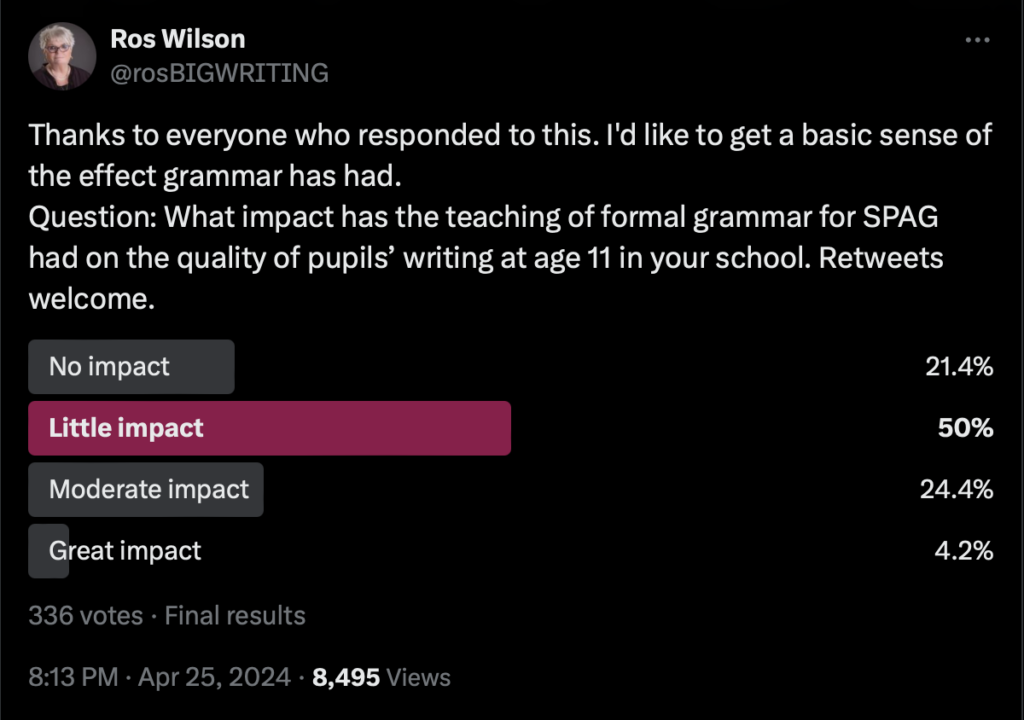

I recently started a Twitter debate about the merits and disadvantages of the formal teaching of technical terminology for grammar. The consensus seemed to be that the only advantages for the teaching of primary aged children were if a school wanted children to perform well in the SPAG tests in Year 6! As ever, there was some advocacy for the benefits for MFL teaching in secondary schools – however, the majority of primary school leaders do not seem to see preparing pupils for success in secondary MFL exams as a priority for primary education.

Over 70% of the colleagues who responded to the poll we circulated on teaching myriad technical grammatical terminology that was included (by statutory requirement) in the revised National Curriculum of 2014 – without consultation – concluded that it had little or no impact on pupils’ writing prowess in Year 6. Indeed, a significant number of comments indicated that writing had lost a lot of its zest and had become more of a technical chore. Over 20% of respondents thought the benefits were minimal to none. One comment noted improvement to understanding rules of punctuation and the others related to later benefits in secondary education.

If children already have a good understanding of more complex grammatical structures and are able to use them effectively in their writing, then the later learning of the formal terminology is made easier and has purpose and meaning. The problem with the grammar requirements imposed is that they require the formal teaching first and then the later explanation of what it means and why a writer might need it. It reminds me strongly of the textbooks we used for learning grammar when I was at secondary school back in the 1950s.

Thinking of these led me to google grammar textbooks of the 1950s and to my surprise the search picked up on grammar today, and the first items identified were all blogs or similar by esteemed writers or educators criticising the imposition of the technical grammar for SPAG.

Michael Rosen’s blog of March 2016 makes protest about the introduction of SPAG. He provides a sample 11 plus paper from that era and says:

You can see what kind of ‘grammar’ questions we had in the 11 plus exams in the 1950s here. It was limited, as I have said, mostly to using the simplest terms – noun, verb, adjective, adverb… and the simplest stuff on tense. The questions mostly involved ‘filling in the gap’ type, so at least you had the context of that sentence to get it right. I’m not saying that this was ideal either, but it was fairly limited in terms of the amount of time we spent doing it and how much emphasis there was on doing it.

Even so, this was part of the means by which the 1950s system failed at least two-thirds of all children. It is quite unfair of Nick Gibb to claim that this is what’s being ‘brought back’. A much more complex raft of terms and processes are in SPaG and it’s one of the main means by which schools and teachers are being judged.

In ‘The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar’, Rachel Cleary (The Atlantic, 2002) says:

A century of research shows that traditional grammar lessons – those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech – don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers. Yes, they need to learn grammar, but the old-fashioned way does not work. This finding – confirmed in 1984, 2007, and 2012 through reviews of over 250 studies – is consistent among students of all ages, from elementary school through college. For example, one well-regarded study followed three groups of students from 9th to 11th grade where one group had traditional rule-bound lessons, a second received an alternative approach to grammar instruction, and a third received no grammar lessons at all, just more literature and creative writing. The result: No significant differences among the three groups – except that both grammar groups emerged with a strong antipathy to English.

And Rachel was discussing the impact of formal grammar in secondary schools.

In a desperate urge to be democratic and quote both sides of the argument I then put ‘support for teaching technical grammar at primary school’ into the search engine and the following came up: Teaching Technical Grammar Terms Doesn’t Improve Children’s Writing (Dominic Wyse, Teachwire, 2024). Dominic says:

We now have the benefit of a significant amount of research to inform the ways in which writing can, and perhaps should, be taught. I have recently contributed to this research in two ways. Firstly, I’ve undertaken an analysis of the research evidence on whether the teaching of formal grammar helps writing. Secondly, I’ve also undertaken a four-year study of writing from a range of perspectives including philosophical, historical and empirical research studies addressing writing across the life course… In addition to more than 150 individually specified elements of spelling and five pages of detailed specification of grammar (that are statutory), primary teachers in England are required to teach and assess their pupils’ knowledge of a range of terms, including compounds, suffixes, determiners, cohesion, ambiguity, ellipsis, modal verbs and lots more. It is presumably intended that the learning of these terms will help children to write better because they are included in the programme of study for writing, yet the evidence is clear – traditional grammar teaching does not lead to improvements in children’s writing.

All in all, articles and blogs critical of the NC 2014 grammar requirements far outweigh support for the arbitrary decisions of the then non-educationalist Secretary of State for education and confirm my despair that a succession of changes of leadership has failed to address the lack of judgement in the English curriculum criticised by so many. The degree of detail required by the inclusion of technical terminology for grammar in the 2014 NC is absolutely unnecessary for effective writing by pupils up to fourteen years old and has no impact on communication, creativity or composition. This level of learning is only necessary for those seeking higher level qualifications in the area of linguistics.

I conclude this blog with the wisdom of Simon Kidwell, President NAHT, in his blog, published by Teachwire in 2022:

Since 2014 I have spoken to a senior politician at the DfE and to experts in the field of teaching grammar, and I am yet to meet anyone who believes that the current grammar curriculum for primary schools is fit for purpose or age-appropriate. One teacher, Alison Vaughan, commented: “The overloaded grammar curriculum holds back learning for those with poor working memory and slow processing. These students are already working hard to remember punctuation and spelling… They need more time consolidating the basics, not complex terminology.” My colleague, headteacher Michael Tidd, added: “I think some of it is just pointless at primary level (I’m looking at you, subjunctive form!) and ends up being overly simplistic because of that…” Objections extend beyond the classroom, too, with The Times reporting that the government’s key curriculum adviser, Tim Oates, said that there was a “genuine problem about undue complexity in demand” in the content of 2016’s SPaG test. A lot of the issue, then, is with curricular sequencing, or a lack thereof. The teaching timeline for these complex concepts is out of whack, and we need to reconsider at what point we should be expecting our pupils to understand and absorb them.

Simon Kidwell has worked as a headteacher and school principal for 17 years, and has led three successful primary schools to achieve rapid and sustained improvement.

It is distressing to see political leaders, who appear to be totally lacking in knowledge or understanding about the needs and abilities of pupils in primary education, ignore the wealth of knowledge and opinion expressed by primary leaders and experts. If, as Simon Kidwell intimates, the NAHT is ready and able to take the lead in decision making for education, we may at last see curricular reform that reflects the true principles of education for our pupils. Simon closed the powerful 2024 NAHT Conference with the words; “The solutions to the challenges we have exist in this room.” May our talented heads rise to those challenges and bring stability and strength back to our profession.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.